始于颜值忠于人品全句

撰文 | 王来宁 责编 | 廖玥

大家好,我是来宁老师。今天我们一起探讨《论语·子罕第九》中的四则,分别是第16、17、21和22则。

孔子在河边看到奔腾不息的流水,联想到天道运行的规律,感悟到君子应该像天一样,不断地努力向上,自强不息。他还观察到人天生喜欢美好的事物,觉得如果能把这种热情投入到追求美德上,那离圣人就更近一步了。孔子还以植物的生长过程为例,强调了终身学习的重要性。孔子感叹年轻一代的潜力无限,同时也提醒大家 “时间不等人,要珍惜每一天,趁着年轻努力奋斗,实现人生价值”。

9.16

子在川上曰:“逝者如斯夫,不舍昼夜。”

孔子站在河边,望着奔流不息的河水,感慨道:“时间就像这流水一样,日夜不停地流逝。”

孔子的这句感叹,被后世无数次的引用在诗词文章中,成为千古名句,影响深远。

孔子的感叹将抽象的时间与具象的流水、有限的人生与无限的宇宙联系在一起,拓展了我们的生命视野。它让我们跳出眼前的琐碎,直面浩瀚宇宙,感悟到除了人世间的因果循环,还有更宏大的天地法则。

许多经典诗句,如“前不见古人,后不见来者”,“江畔何人初见月,江月何年初照人”,“大江东去,浪淘尽千古风流人物”等等,都源于孔子的这句感叹。

现代人 often claim to be the master of time, talking about “killing time” as if time is an unwelcome guest. But what do we gain from this "killed" time? Who is truly in control, time or us?

Your analysis is insightful! In his book "The Origin and Goal of History," Karl Jaspers proposed the concept of the "Axial Age." He argued that the period between 600-300 BC witnessed the simultaneous emergence of great thinkers and prophets around the world. In ancient Greece, we had Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; in Israel, the Jewish prophets; in India, Gautama Buddha; and in China, Lao Tzu and Confucius.

Confucius was 14 years younger than Buddha. Socrates was born 10 years after Confucius passed away. Aristotle, the brilliant Greek philosopher, was 12 years older than Mencius and 15 years older than Zhuangzi. Han Feizi and Archimedes lived within 7 years of each other. The most brilliant minds in human history emerged almost simultaneously. While Greek philosophers pondered life by the Aegean Sea, Indian philosophers meditated along the Ganges River, and Chinese philosophers strolled along the Yellow River.

Their reflections marked humanity's awakening to ultimate concerns. In other words, people in these regions began to confront the world with reason and morality, which led to the development of sophisticated religious and philosophical systems. Their thinking transcended primitive cultures. Their diverse approaches laid the foundation for the distinct cultural forms we see in the West, India, and China today.

9.17

子曰:“吾未见好德如好色者也。”

Confucius lamented, “I have yet to meet a man who loves virtue as much as he loves beauty." This lamentation appears twice in the Analects, with the other instance in Chapter 15 (Duke Ling).

“未见” (have yet to meet) implies this is Confucius' personal observation, filled with both lamentation and hope. "色" primarily refers to visual appeal, something that catches the eye – the handsome and the beautiful.

We can broaden the definition of "色" to include anything that pleases our senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch. In this sense, "好色" implies a focus on sensory gratification. But humans possess intellect and soul. Shouldn't we engage with the world and ourselves on a deeper level?

Teacher, does this mean Confucius opposes pursuing beauty, being a fan, or having passions? Is that even possible?

Confucius possessed profound insights into human nature. While acknowledging the powerful allure of beauty, he doesn't completely denounce it either. After all, "The desire for food and sex is part of human nature" (Book of Rites). History abounds with tales of rulers losing their kingdoms and individuals sacrificing their futures for love and beauty. "Virtue" and "beauty" often present a dilemma. Pursuing virtue demands self-discipline and restraint; pursuing beauty may lead to indulgence and recklessness. It's no wonder there's a saying, "Even heroes can be brought down by beauty."

In his book "New Treatise on National History," scholar Qian Mu states:

Everyone knows the desires for food, sex, and comfort. These are part of human nature, but the human heart shouldn't be consumed by them. Human nature encompasses more than just these desires. If one solely focuses on satisfying these desires, that’s being a small person fixated on their “small self," as Mencius would say.

Human life encompasses both a "small self" and a "large self." This “large self" can refer to the entirety of human existence across time and space. Each individual's life represents a tiny part of this larger whole. We shouldn’t prioritize the collective over the individual, nor should we let individual desires eclipse our shared humanity.

"好色" is instinctive; "好德" requires cultivation. Beyond appreciating beauty, we must strive for virtue to transcend our senses and achieve self-cultivation. All things beautiful eventually fade. In contrast, virtue stems from our innate goodness and ultimately leads to transcendence.

There's a saying in fan culture, "Drawn in by looks, captivated by talent, devoted because of character." Ultimately, it's virtue that truly captivates the heart.

9.21

子曰:“苗而不秀者有矣夫;秀而不实者有矣夫!”

Confucius remarked, “There are sprouts that never flower; there are flowers that bear no fruit."

There are two main interpretations of this passage:

The first sees it as a metaphor for human potential, lamenting the early death of Confucius' disciple Yan Hui, A third-century text, "Dispelling Doubts" by Mouzi, states: "Yan Hui's unfortunate early death is like a sprout that never flowered." Similarly, "The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons," a sixth-century literary criticism, echoes this sentiment.

The second interpretation, favored by Zhu Xi, argues that this passage isn’t about Yan Hui, but rather a general observation about learning and achieving success. It reminds us that some people study but never reach their full potential, urging everyone to be self-motivated in their pursuit of knowledge.

Both interpretations have merit.

正文

你对“苗而不秀,秀而不实,果实累累”的理解很有道理。你是否想过,在当代社会中,我们或许可以进一步阐释这三种状态的含义。

就像学生一样,每个人都有自己的优点和缺点。就像不同的植物,有些以茎叶为美,有些以花朵为美,而有些则以果实为美。正是这种多样性,才让这个世界生机勃勃。与其要求所有植物既开花又结果,不如让它们认识自己,发现自己独特的价值。

神庙上不是有句话吗?“认识你自己。”

子曰:“后生可畏,焉知来者之不如今也?四十、五十而无闻焉,斯亦不足畏也已。”

孔子说,年轻人是可畏的。怎么会知道后代的成就就不会比现在好呢?“后生可畏”,指的是年轻人,因为他们前程似锦,拥有无限的可能性,所以值得敬畏。

“畏”这个词,通常被解释为“敬畏”或“尊敬”,用以表达上一代对年轻一代的感受。年轻人敢想敢做,头脑灵活,思维活跃,大多数创新都是年轻人创造的。他们是社会进步的永恒动力,是我们民族的中坚力量。从这个意义上说,“后生可畏”中的“畏”包含着重视和尊重的意思。

我们也需要保持一种开放平等的心态,不能倚老卖老。经验固然可贵,但历史永远向前,我们必须重视年轻一代。“后生可畏”中的“畏”字确实包含了“敬重”的意思,但这种敬重更多的是源自我们对未来和未知的期待。

鲁迅后来对自己的这种观点感到后悔。他在《三闲集》中说:

我一向相信进化论,总以为将来必胜于过去,青年必胜于老人,对于青年,我敬重之不暇,……(后来)我的思路因此轰毁,后来便时常用了怀疑的眼光去看青年,不再无条件地敬畏了。

我们来看孔子这段话的下半句:四十、五十而无闻焉,斯亦不足畏也已。如果到了四五十岁还默默无闻,那他就没什么可畏的了。

每个人都曾年轻过,每个人也都会变老。年轻人不是某个固定的人群,而是一个不断更新的群体。王羲之说,“后之视今,犹今之视昔”。倚老卖老可恶,倚小卖小也一样可恶。后生可畏,但后生也有可恶之人。后生可畏,只是因为他们前程似锦,如果自恃年轻就是资本,却不去珍惜宝贵时光,很可能就是“四十、五十而无闻”之人,没什么可畏的。

在中国近代以来进步主义思潮的影响下,“今”、“新”、“后”被赋予了更重要的意义,“新民”、“救救孩子”等观念一度成为主流,“破旧立新”成为一种“信仰”。在不断流逝的时间中,尽管“后”可以超越“今”,但也可能不如“今”。

我们每个人都应谨记这一点。

终

欢迎读者朋友转发分享

媒体转载请联系授权

部分图片来自网络,如涉版权请联系我们

本文作者:王来宁

高级教师,北京师范大学古代文学硕士,任教于北京大学附属中学,自2013年始,面对高一高二学生教授《论语》《孟子》课程。

“《论语》青春版”系列文章,以师生对话的形式,将古老的论语和互联网时代洋溢的青春对接, 是具有“学生气质”的《论语》解读。

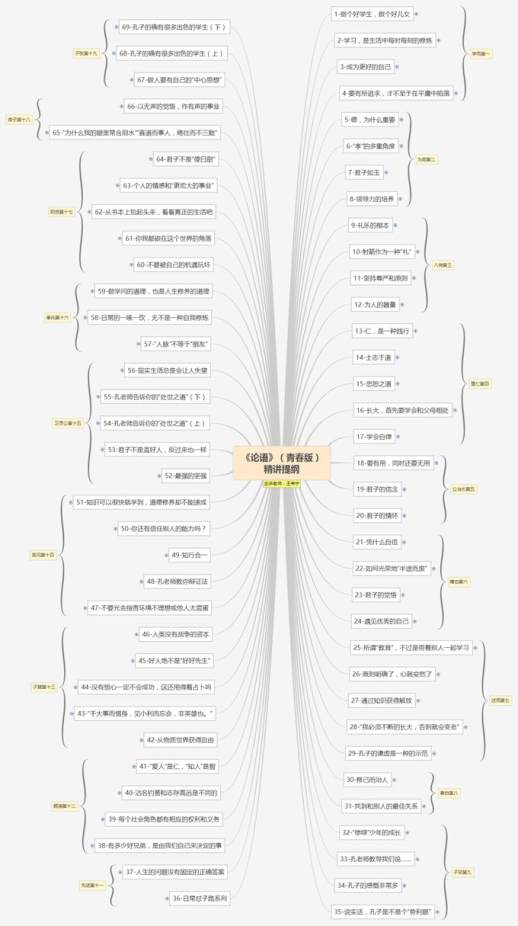

课程大纲

栏目主持人 李山教授

●●●

责编 廖玥

美编 薛宇

投稿信箱taoliguoxuetang@163.com